It seems on a weekly basis that publications introduce us to some new term that describes an unruly practice within the pharmacy benefit landscape. Clawbacks, spread, gag clauses and others dominate the headlines, with advocates for the many stakeholders in the pharmacy supply chain lining up to either launch an assault or defend their turf. Since the “purchaser” voice is usually absent from these national discussions, we have provided a high-level overview below.

CLAWBACKS

Clawbacks can arise in multiple scenarios, but most often occur when a patient is on a benefit plan that requires a minimum copayment regardless of the actual cost of the drug. While processing a prescription, the retail pharmacy sends information about the prescription to the individual’s PBM. The PBM then tells the pharmacy the amount of the copay or cost sharing that it must collect from the patient. When the collected copay is more than the pharmacy’s contracted reimbursement, the PBM reduces the pharmacy reimbursement by this difference. This reduction is referred to as the clawback. In some scenarios the PBM may keep these funds. In others, they are passed back to the insurance company or plan sponsor. Regardless, in most cases the patient is paying more than he/she would if the insurance plan was not being utilized.

GAG CLAUSES

On October 10, 2018, President Trump signed into law the Patient Right to Know Drug Prices Act. The act removes the ability for a PBM to enforce a contractual clause prohibiting a pharmacy from telling a covered individual the difference between his/her out-of-pocket cost for a medication and what the cost of the medication would be without insurance coverage. These clauses are better known as “gag” clauses. Community pharmacists argue that gag clauses allow PBMs and insurance companies to overcharge patients. PBMs acknowledge that there is confidentiality language in its contracts but argue that the practice of charging minimum copays when the cash price is lower is a plan design decision made by the plan sponsor and is rare due to lowest of logic provisions. One recent study showed that patients are charged more than the cash price of the drug approximately 25 percent of the time, but it is unknown how much of that study’s data were from fully-insured plan designs that required a minimum copay.

The likely impact to self-funded plan sponsors is minimal if any. Since Walmart’s introduction of its $4 generic drug program in 2006, most PBM contracts have included a “lowest of” provision where the plan is billed the lowest of the drug’s discounted cost or the pharmacy’s usual and customary price (U&C). In addition, many plan sponsors apply lowest-of logic to the application of a participant’s cost share in its plan design. In many retail pharmacy agreements with PBMs, the U&C is defined as, “the price the pharmacy would charge a cash-paying customer for the same prescription.” The “Patient Right to Know Drug Prices was approved by a near unanimous vote in Congress and all stakeholders, including PBMs, supported the legislation.

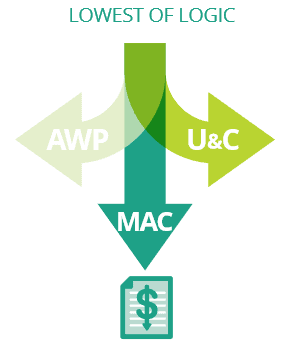

LOWEST OF LOGIC

Lowest of logic is both a contractual clause and a plan design decision. The contractual clause requires a PBM to invoice the plan sponsor the lowest price among the discounted average wholesale price (AWP), the pharmacy’s usual and customary price (U&C) or the maximum allowable cost (MAC). Plan design setup determines what cost is paid by the participant at the point of sale. When lowest of logic is implemented, a plan participant will be charged the invoiced cost to the plan or the participant’s cost share, whichever is lower. When this clause exists in the PBM contract and the plan design, and when retail pharmacies are submitting their cash price as required by their network agreements, the participant should not pay more than the price he/she would otherwise pay without using insurance. This does not include prices associated with retail pharmacy membership programs or drug discount cards like GoodRx, which is an entirely separate conversation.

SPREAD

It is important to remember that the PBM determines the price it will reimburse a retail network pharmacy and the price it will invoice a plan sponsor on any given transaction, so long as it stays within the confines of its contractual arrangements. Retail spread occurs when the amount the PBM reimburses the retail pharmacy is less than the amount the PBM charges the plan sponsor. Certainly, this spread on retail claims is not the only place that a PBM can produce margin, but it is a common practice. Under a traditional deal, negotiated discount guarantees are set forth in the contract, regardless of which pharmacy fills the prescription for participants. This benefits the plan sponsor because it provides a level of stability and certainty around its drug costs by taking channel and drug mix out of the pricing equation. The PBM puts itself at risk to hit the contracted guarantees. While the PBM is at risk for not hitting its guarantees, it benefits in circumstances when its payment to the pharmacy is less than the price it has guaranteed in its contract with the employer. Under a basic pass-through deal, the PBM invoices the plan sponsor whatever it reimbursed the pharmacy. As the PBM cannot derive revenue from spread, it charges an administrative fee to the plan to cover the cost of its services. While there may be overall discount guarantees in the contract, they are typically lower than those set in a traditional deal, so the plan sponsor is at risk for its participants utilizing high cost versus low cost pharmacies.

It is possible to manage a traditional model with spread so that the total costs to the plan are less than a pass-through model. It is also possible for a pass-through model to generate savings, particularly for plans with limited networks, on-site pharmacies or who wish to direct contract with local pharmacies. Regardless, the model should be aligned with delivering the lowest net cost to the plan and its participants.

REBATES

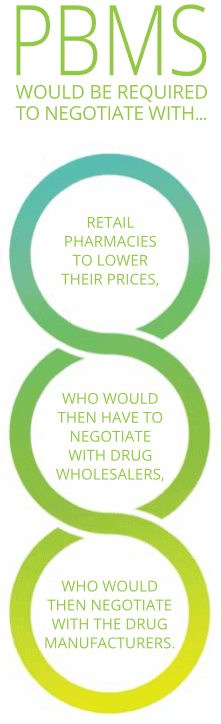

Rebates are produced through a mechanism that allow PBMs, on behalf of their plan sponsor clients, to negotiate directly with drug manufacturers to reduce the price of brand name drugs. Without this ability to negotiate directly with manufacturers, PBMs would be required to negotiate with retail pharmacies to lower their prices, who would then have to negotiate with drug wholesalers, who would then negotiate with the drug manufacturers. Historical performance and an underlying knowledge of the supply chain would suggest that these intermediate entities are not interested in lowering drug prices under the current system. While plan sponsors should want to preserve the mechanism of negotiating directly with manufacturers for additional discounts, there is no debate that the inflation of list prices and their corresponding rebates has risen to a level of absurdness. Complicating the issue is the practice of PBMs and health insurance companies of keeping all or part of the rebates tied to a plan sponsor’s utilization. In these cases, the PBM directly benefits as rebates grow. Further complicating the matter are contractual rebate guarantees that PBMs have with plan sponsors, particularly those guarantees for future years of the contract term. Under these arrangements, the PBM has set the guarantees based on its expectation of the plan’s rebate yield, both in the short and long term. As new drugs come to market in established therapeutic classes with lower list prices and lower rebate values, it is difficult for a PBM to add these drugs to its formulary without renegotiating the rebate guarantees in its contracts with plan sponsors. Without adequate transparency of the drug-level rebates and appropriate analytics, many plan sponsors see taking a reduction in rebate guarantees as a negative. A final topic under the rebate category is the implementation of point-of-sale rebates. Point-of-sale rebate models apply an estimate of the drug-level rebate at the time the claim is processed. Since the value of the rebate is typically applied before a participant’s cost share is calculated, it can result in a reduction of a participant’s out-of-pocket costs.

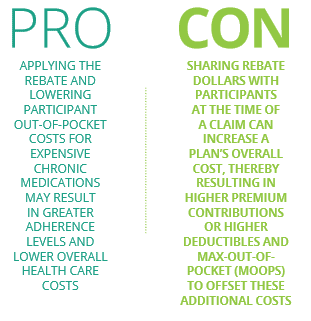

There are pros and cons to this approach. The obvious pro is that applying the rebate and lowering participant out-of-pocket costs for expensive chronic medications may result in greater adherence levels and lower overall health care costs. An obvious con is that sharing rebate dollars with participants at the time of a claim can increase a plan’s overall cost, thereby resulting in higher premium contributions or higher deductibles and max-out-of-pocket (MOOPs) to offset these additional costs. While the approach seems very logical, there are a host of other considerations for plan sponsors. Mike Stull’s recent article, Now or Later: Rebate Considerations for Plan Sponsors, covers this topic in more depth.

To summarize, rebates are an important part of the drug pricing model. Plan sponsors should balance the desire for additional rebates with sound clinical and formulary management that ensures the plan and its participants are achieving lowest net cost.

INDEPENDENT/COMMUNITY PHARMACY ASSOCIATIONS

Independent and community pharmacies have served an important role in the delivery of medications and trusted advice to patients. They also have an active voice in local, state and national politics, seeking to enact policies that allow them to better compete against the national chains. Typically, these policies call for increased reimbursement for the pharmacies and lower earnings for the PBMs. The impact of these policies on prices to plans and patients is relatively unknown, but one could guess that prices would likely increase over time.

Articles written by or in conjunction with the pharmacy associations should be read within the context of their bias and ultimate goal of higher reimbursements. Within a state, these organizations tend to have strong voices with media outlets and state legislators. From a state legislator’s perspective, defending the “little guy” against a large, out-of-state competitor using new regulations claiming to protect consumers/taxpayers plays well on both sides of the aisle. Thus, this creates the opportunity for legislation to be passed and allows legislators to show superficial accomplishment. Whether these regulations ultimately lead to lower prices for patients is yet to be conclusively proven.

As with many public policy debates, the underlying issue is much more complex than the headlines or talking points. To be clear, retail pharmacy associations are not advocating for plan sponsors, and it has been shown that in some cases these independent pharmacies are actually reimbursed more than national retail chains, particularly those owned by the PBM. This becomes confusing when the independent pharmacy claims it’s not being reimbursed enough to cover its acquisition costs, which seems to imply a procurement challenge in addition to the reimbursement challenge.

Thus, while a news article may evoke sympathy for the challenges (and there are many) independent pharmacies face, plan sponsors must evaluate reimbursement in a much larger context.

THE EMPLOYERS HEALTH APPROACH

The Employers Health approach is focused on helping plan sponsors minimize risk and maximize value by finding balance among pricing model, participant affordability and disruption and sound clinical management. Employers Health offers multiple pricing models based on the unique needs of each plan sponsor. Participating groups benefit from an annual market check negotiated by Employers Health to refresh and update pricing and contractual terms as the market changes. Participating groups also benefit from audits that verify the PBM contracts are performing as they should. While the PBMs have the opportunity to generate revenue in certain areas, the contract is negotiated and managed in a manner to yield the lowest overall net cost to the plan and its participants.

Download Insight